Anti-Asian racism harms individuals, community

April 10, 2021

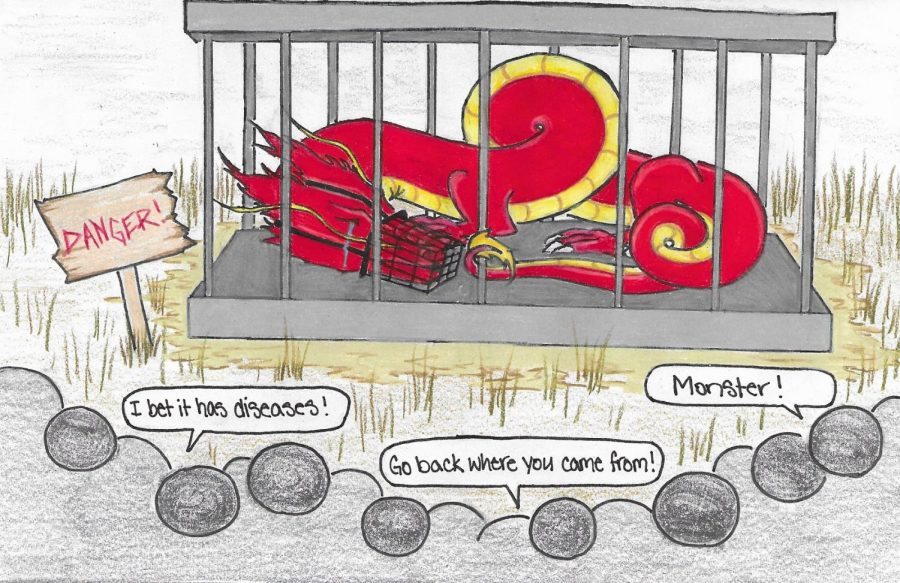

Social media feeds are flooding with videos and photos of Asians being harassed across America, images of grandmothers being punched in the face, sisters being spat on, Asians dying because of hate.

A recent report by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino, in an analysis of hate crimes during the month of March in 16 major American cities, stated attacks targeting Asians increased by 145 percent.

The source of this rise in crime against Asians can be traced to the beginning of the pandemic. On Jan. 31 of last year, the United States restricted travel to China. As panic grew in response to the pandemic, theories of the origin of COVID-19 ended up focusing on China. The news kept China in the spotlight, encouraging the fear of the country, and by association, all of Asia and the people who hail from there. This fear, fueled by anti-Asian rhetoric from government officials and some media, turned to hate.

COVID-19 is mockingly called the “China virus” or the “Kung Flu,” and Asian Americans are being attacked because of a virus, a pandemic over which they have no control. Children of all Asian ethnicities in schools are being bullied for their culture and heritage, while adults and elders are being assaulted on the streets.

While the CSUSB analysis focuses on major American cities, these experiences are not limited to those places. Students, staff and alumni are facing racism in Fort Collins.

Dehumanizing incidents

Language arts teacher Tiana Song, who identifies as Korean American, experienced anti-Asian racism in June. In JAX Ranch and Home, Song and her son were in an aisle with another family who were not wearing masks. Song’s six-year-old son was trying to avoid the other children and socially distance himself from them, and was getting frustrated when they would come close to him and he had to back away. He expressed this frustration to Song, and the mother of the family overheard and came to confront Song. She accused Song and her son of violating her rights.

“It’s my right not to wear a mask,” the woman told Song. “I live in a free country. You should go back to China, take that virus with you.”

The encounter escalated from there.

“She’s like, ‘What? Do you wear a mask because you fear for your life?’” Song described. “She’s like, ‘I hope Donald Trump deports all of you Chinese or maybe even better yet, has all of you—she didn’t use the word kill. She pretty much implied if he’s not going to deport us back to the country where we came from, then, you know, hopefully he’ll get rid of us for good or something like that.”

This experience was jarring for Song.

“I have never ever had someone dehumanize me before based on my race,” Song said. “I mean she was cursing at me. I mean this woman was screaming at me. I mean she spit at me. She didn’t get it on me; it was on the floor towards me but I was just like, ‘What is going on?’ and [she was] telling me to be deported or better yet, dead.”

When Song processed the attack, she was filled with multiple emotions.

“I don’t even know if I could say I was angry,” Song explained. “I think I was very disappointed. I think I had a little bit more empathy for people in this country that fear for their lives every single day just because of the way they look. I’ve never felt that before and I feel like I only even got a tiny glimpse of that—that type of hatred—the fact that she felt empowered to hate me.”

Such empowerment has been bolstered by the Asian hatred spreading through social media.

Kimberly Ming, a 2007 graduate and co-founder of the MixdGen Podcast, a show dedicated to sharing the stories of multicultural, mixed race and interracial families and friends in an effort to educate and promote inclusivity, noticed the rise in anti-Asian content online.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Ming, who identifies as Chinese Puerto Rican American, found a post on Instagram that suggested COVID-19 was spread by the Chinese because they eat soup containing bats. In this misinformation, Ming recognized a tactic similar to the approach of Song’s attacker.

“I felt like there’s a tinge of strategy to dehumanize, and I still think that’s kind of embedded into the American lens of racism,” Ming said.

Ming has even seen a reflection of the cultural shift toward racism in her family.

“Well, family members, even, were mad at another family member, and basically degraded us by calling us ‘gooks,’ which is a racial slur. And so I remember hearing that voicemail and being like, ‘Wow that was really hurtful,’ and that’s from someone that I’m living with,” Ming said.

As hatred toward Asian Americans has become a bigger threat in Fort Collins, senior Felix Yu, a Chinese American, has begun to worry for others in the community.

“One person I know about had something thrown over their yard that said, ‘Go back to your country.’ And that’s something new, like a direct attack, on Asian heritage, Asian culture,” Yu said. “It’s concerning—not just for me—I’m not as worried about it because I know they’re less likely to attack me, but I’m worried about my grandparents who don’t speak much English, who don’t conform to that view of an American.”

A history of anti-Asian racism

While the recent attacks on Asian Americans are new, anti-Asian racism is not. Since Asians first migrated to America in the mid-1800s, many have been subject to hate. Chinese immigrants were often victims of attacks and were given dangerous jobs. In the building of the Northern Pacific railroad, Chinese laborers were paid less than white men, slept in tents as opposed to the train cars for white laborers and were tasked with the job of blowing up the mountains and rock that stood in the way of the railroad tracks. During World War II and after, Japanese Americans were subjected to the hatred fostered during the war.

“So I guess pre-COVID, there’s all this history that goes with racism against Asians, specifically. I think it gets downplayed in our history; it’s not spoken about very often, but that kind of stems from this idea where the Asian model minority myth comes into play,” Song said.

The model minority myth is the belief that Asians are the example other minorities should try to follow.

A key aspect of the model minority myth is that Asians are “quiet.” This can lead to people believing that Asians will simply not fight racism for fear of consequences. Many Japanese Americans were terrified of being sent back to the concentration camps, and went about their lives as quietly as possible, taking all the hate silently.

“It’s difficult to speak out, because sometimes, honestly, it feels like it’s not enough to speak out,” Yu said. “That’s like a big thing where like the things that people said or they’ve done, it doesn’t hurt enough or it doesn’t feel enough to actually take action against it.”

Part of the issue is these xenophobic behaviors have been accepted as commonplace in America.

“It’s kind of like a normalized thing I guess, just like little quips and comments. It’s like nothing that is life threatening but it’s like, ‘Oh you call me by the wrong name’ or things like calling me the c-word [chink] or things like that. That’s just the stuff I faced growing up,” Yu explained.

Another main factor of the model minority myth is the belief that Asians are the “smart ones.”

“It’s totally downplayed or it’s seen as like well it’s not so bad,” Song said. “This idea that it’s a positive stereotype at least. I mean I’ve had people say that to me before that ‘Well it’s not a bad thing that I assume you’re smart because you’re Asian,’ and I’m like, ‘What?!’ You know it’s unbelievable, but I think people see it. It’s not like I’m calling you a criminal, based on your race, I just assumed that you’re smart.”

Any stereotype, whether it is perceived as positive or negative, is detrimental according to Ming.

“I know my sister faced some things where she was assumed that she was smarter than everyone else. In math, specifically, which I think is also still like a negative stereotype, even though people think they’re complimenting you but I think there’s a negativity around assuming we’re all the same,” Ming said.

The assumption minimizes Yu’s ability to take pride in his accomplishments.

“There isn’t a worst moment for me, it’s just an accumulation of things. I think the worst moment is honestly just knowing that I have this stereotype,” Yu said. “I go around and I know that ‘Oh, I’m considered nerdy because of my race’ or, because I’ve done well is because I’m Asian. I think that’s probably the worst thing is knowing the stereotype is there and you can’t really do much about it but you just have to keep going.”

Finding a solution

Whether the incidents involve violence or verbal harassment, the feeling of being seen as lesser simply because of race is painful.

“I think it’s like a knot in my stomach, maybe in my heart and in my throat. Maybe a three-tiered knot going up—thinking about all my feelings in my body, and I think it’s like the feeling in my stomach makes me feel kind of just disgusted,” Ming explained. “But the knot in my heart, I think, is the hurt, and then in my throat, it’s like what do you say because sometimes when someone does anything that’s racial, where it’s trying to be intimidating, you feel it in all those places of sadness but also disgust. But sometimes it’s hard to know what to say.”

For many it can also be difficult to know what to do.

“I think the hardest part of being Asian in America is trying to address those stereotypes and be taken seriously,” Yu said. “I think it’s tough to know that you’re going to be made fun of based on how you look or how people think of you, but when you try to find other people or speak out, you’re taken less seriously. So, that’s something that is kind of unique to being Asian American in America.”

To begin finding a solution, Yu suggests learning more about Asian Americans.

“I think just understanding what Asian Americans go through and kind of being aware before you say something or do something is important. And empathizing with an Asian American and understanding that their culture may be a little different, but it’s still a valid culture,” Yu said. “You may talk differently than me, you may look differently than me but we can still get along and have a good time.”

The effort to respect and understand other cultures forms the basis of Ming’s approach as well.

“Why are you trying to figure out why that person is different from you? Just treat them like anyone else from your own racial group and get to know who they are,” she advised. “I think that’s one great step. And then, holistically, I think it’s trying to be self observant and see how maybe they didn’t realize but they were stereotyping Asian Americans, and then try to look internally to try to learn more in the humanizing manner, to just understand from a culturally-rich perspective, who we are as a very diverse community.”